Written By Tiernan Ray

You may have heard that the White House this past week threw its support behind a bipartisan Senate proposal for infrastructure. Among many other things, the proposal has sixty-five billion dollars earmarked for developing the nation’s broadband infrastructure.

“It is just an astronomical number,” says Cheri Beranek, chief executive of Clearfield, which sells fiber-optic equipment to connect homes and businesses to broadband networks.

For a company that may have $125 million in sales this year, the top end of Clearfield’s official revenue forecast, such plentiful spending could prove a significant windfall.

“The message to think through as an investor is that the initiatives that are going on right now with government funding are not about short-term issues,“ Beranek tells me in a recent video meeting. “They’re talking about how do we future-proof broadband.”

What does that mean? On a prosaic level, there is a sudden urgency to make sure everyone can run Microsoft Teams, the program via which Beranek and I were talking, or Zoom, with adequate quality. The two of us shut off our video shortly into the conversation because the audio was stuttering. That’s unacceptable.

Only about a fifth to a quarter of homes in the U.S. are wired with fiber that will allow a gigabit per second of service, which is what people really need to be productive, observes Beranek.

“We're going to see a high number of homes that are going to be connected, and businesses that are going to be connected, over the next five years,” to close that gap, she says.

“The time for broadband deployment right now isn’t a question of if, it’s a question of how fast,” Beranek says. “And that's really what the pandemic has proven.”

But this is about something more, what Beranek believes is a wholesale change in the computing capability of the networks to which most people have access.

Computer maker Sun Microsystems used to have a slogan, “The network is the computer.” What Beranek describes is akin to that, where computing resources get pushed closer to customers rather than being concentrated in a central office, or in the cloud, which is the modern equivalent of the telco central office.

“An important part of computing is going to be about being able to get electronics further and further out into the network,” explains Beranek. By further out, she means, at the places where the network comes closer to the end user, the “edge” of the network.

“It’s still about fiber, but it’s also about the new way that computing is done.”

Pushing that change, she argues, is the fact that the pandemic has set in motion a lifestyle shift that is going to ripple through society.

“The lifestyle is going to be about data, about the immediacy of that data, and edge computing is the next layer to make that happen; we want to be part of edge computing.”

It is also the start of a decade or more of investment that could transform the American heartland, the rural areas where Clearfield has made a name for itself helping to close the digital divide.

“We’ve done this before,” she says of federal funding. “We need to think back a hundred years, and how electricity was brought into the country,” says Beranek. “They were never going to string electrical wires throughout Alaska if there wasn't support” from the government, “or through Montana, or for that matter, to a lot of rural parts of Minnesota.”

“But, it gave a tax base, and it gave an economic base to really globalize what the U.S. would be capable of doing.”

The installation of fiber itself can create new jobs, a craft industry of learning to splice and run cable somewhat akin to the Works Progress Administration of the 1930s.

“It'll certainly create a new jobs initiative that can really provide an extremely strong living wage for people who are good with their hands, and didn’t necessarily have to go to college to earn a living,” says Beranek.

Clearfield, which is based in Minneapolis, didn’t stumble on a sudden enthusiasm for the heartland. “Over our twelve years of existence, we built the company on the foundation of the seven hundred service providers in the U.S.” that wire up communities, she notes.

Many of the employees know the heartland well. Beranek came from a small town in Minnesota, and has seen her kids move back to the countryside to raise families. She is convinced much of the country will make some form of work from home permanent, at least on a partial basis.

“We’ve proven we can work from home, and work in a way that is conducive,” says Beranek, speaking of society in general. While people will still gather in offices for what she calls “that tribal learning,” nevertheless, “people are going to be working from home for three or four days” out of a week, she contends.

“I'm seeing a lot of people go back to my hometown, and people talking about not having to live in downtown Minneapolis,” she observes. “Others are choosing to live in downtown Minneapolis because of the lifestyle there that they want.”

“I think the word lifestyle is an important matter moving forward,” she says, “in that people are going to choose the lifestyle that fits their personality, not the lifestyle that fits necessarily how they have to earn their income.”

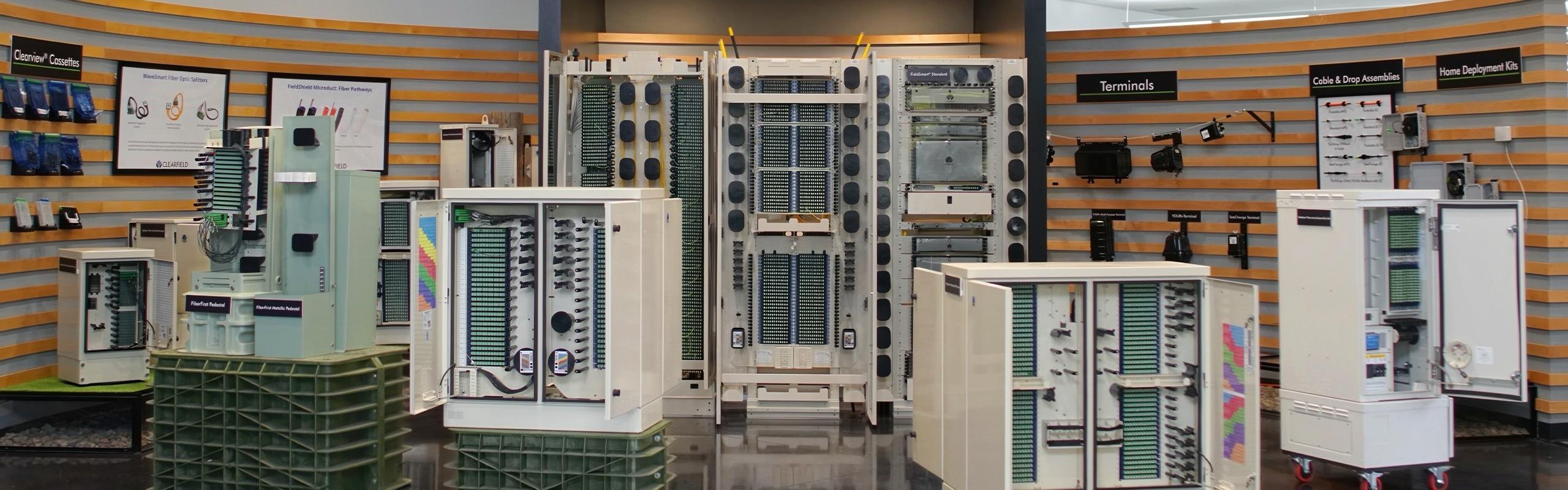

The potential for new computing, and a massive influx of funding, comes at an interesting time for Clearfield, when its market has already shifted into high gear. Clearfield’s products extend the operators’ networks out into the so-called last mile, the spot where fiber optics enters homes, schools, businesses.

The pandemic means that local telcos and utilities have an added urgency for Clearfield’s products. Sales growth has surged, to forty-three percent in the latest quarter, and profit margins have expanded, helped in part by the ramp-down of travel and entertainment expenses, but also by the increasing value of the company’s products.

The seasons of Clearfield’s business are a bit like planting and harvest. Last year, the operators focused on lighting up connections of homes and business already on their network who started to take service. This year, they are starting to plant again, that is to say, to build for next year’s harvest.

Clearfield had enough “visibility” to resume offering a financial forecast in April. Customers of Clearfield are starting to lay the groundwork for passing more homes. “As the year has gone on, we’ve seen a lot more work in regard to the get-ready for next year,” says Beranek. Enough “to be able to envision what we're going to be able to service over the winter and into next year.”

A good company rolls with the punches, and Clearfield has been able to keep its momentum even as some markets have not cooperated. In additional to serving the local and regional operators, Clearfield sells to the majors, Verizon and AT&T, whom Beranek regards as very good customers.

Fiber-optic connections are a direct way to exploit 5G wireless because cell sites need to be fed by fiber. And so the 5G proliferation that was supposed to be underway right now was going to be a great opportunity.

But during the pandemic, the carriers held off on deploying much of that infrastructure, and the time frame for some 5G development is still uncertain. In Clearfield’s most recent quarter, ended in March, sales to the national carriers were down forty-two percent from the year-earlier period.

Now, AT&T, she observes, is placing new emphasis on fiber to the home, because they’ve found those subscribers are more highly valued by the Street. Second-tier operators such as Windstream and Frontier, likewise, “are seeing that if they can turn their copper subscribers into fiber subscribers, those become much higher rates of return for them.”

There’s also a heightened emphasis on so-called fixed wireless, a signal beamed into a home or business, rather than the so-called small cells that everyone has been expecting to be built out for mobility in dense urban environments. Fixed wireless also needs fiber to back-haul its connections.

In the three times I’ve interviewed Beranek in the past three years, she has shown herself to be an astute observer of the inside baseball of telecom, and a realist about how plans change. The shifts in market approach don’t appear to faze her. She now believes that some product that would have been sold directly to Verizon and AT&T may end up being more of an indirect sale, if you will.

“We think that community broadband actually may be the way in which we can best leverage an entry point into 5G,” she says, “because community broadband are putting in place an amount of fiber to each home that will be able to be leveraged for future 5G deployment that the carriers come through with.”

The important point for investors, she says, is that “fiber is going to be an asset” in many, many ways.

The new government money coming into the market will be apportioned to the telcos and cable operators and utilities, who in turn will spend some of it on equipment from Clearfield as well as others.

The support includes not just the bipartisan deal taking shape now, but also a previous initiative, the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund, a ten-year, twenty-billion-dollar federal program to develop Internet connectivity in rural areas. The first tranche of RDOF money, nine billion, starts getting distributed next year, upward of half a billion every year.

Out of the half a billion, Clearfield can go after about ten percent, she believes. “There is an incremental fifty to sixty million dollars a year for us to be able to go after,” she says. “The Biden bill will be over and above that.”

Come 2025, the new infrastructure bill being debated now, if it is passed, will be dishing out money in conjunction with the RDOF, amplifying the effect for Clearfield.

Beranek is quick to point out that the money is not meant to replace commercial interests. “It’s not about competing with for-profit service providers, but establishing public-private partnerships so that we can leverage what for-profit knows how to do, and knows how to do well,” she says, “but leverage the dollars available from government initiatives so that we can grow economically and return those dollars back into the market.”

Clearfield itself has grown profitably serving an under-served market for the entirety of its existence. On thirty percent sales growth this year, the company may notch something like sixteen percent operating profit margin, the Street thinks.

“I really want to promote that pillar, the operational efficiency,” she says. “We built the company so that we could scale this way when demand hit,” she says. With COVID-19 and work from home, demand exploded, as they say.

A rush of new money could be a challenge for a company of just 250 employees. But with twelve years of operating experience, starting from just four million dollars in the bank but now having a balance sheet of sixty million, and no debt, the business is ready to grow, says Beranek.

Clearfield runs three different manufacturing plants, one in the U.S. and another two in Mexico. Proof of the resourcefulness of the company was its ability to come through the pandemic without missing a beat in any of those facilities despite global component shortages.

“We always keep six months of inventory of the resources we need,” she observes. That got cut in half during the pandemic. “It makes one a little nervous, but we were fine.”

Little things can become a big deal in a pandemic. Clearfield’s cabinet product, for organizing fiber in the field, comes with a screwdriver inside the front door of the cabinet. The sudden resumption of economic activity this spring led to a global shortage of hammers and screwdrivers.

Because Clearfield couldn’t find screwdrivers anywhere in the world, “We commissioned the making of a Clearfield-designed screwdriver by a precision stamping house in Germany,” she recalls. “You gotta do what you gotta do.”

Such experiences make a good company better.

“We're a much better-run company today at a hundred and twenty million dollars [in revenue] than we were when we were a thirty-million-dollar business,” observes Beranek. “We've got more systems and processes in place, less personality.”

Being part of the evolution of computing will prompt an evolution of the company’s products over many years, potentially making them much more valuable.

The company has made a name for itself by taking costs out of stringing fiber. Most of those products are what are known as “passive” fiber optics. They help organize strands of fiber without affecting the signal itself, the photons traveling through the fiber.

For example, Clearfield’s “cassette,” a compact plastic sandwich of trays seven inches by eight inches by one inch, lets a technician splice together fibers without the need for a separate piece of equipment called a vault. The company estimates the cassette can cut a third of the time it takes to splice fibers, taking out a fifth of the total cost.

For edge computing, where electronics have to be moved closer to a customer, more of Clearfield’s products will over time have to be “active,” meaning they will contain electronic components to shape the signals and perhaps even perform calculations near the customer rather than send data all the way back to a central computing facility.

“There will be additional products, and it’s not about next year’s revenue, it’s a decade-level build out,” says Beranek.

“An investment in Clearfield is about a company that is helping to build the fiber infrastructure of today for tomorrow's computing requirements that will need new kinds of connectivity.”

Chasing growth sometimes brings with it big spending as well. The Street often views that as a big opportunity to do big banking deals, by advising on M&A. So far, Beranek has refused to follow that playbook.

She expects acquisitions will be part of Clearfield’s expansion, but Beranek is in no hurry to splurge on buying companies. Clearfield has not been “tapping the balance sheet,” meaning, multiple rounds of follow-on equity raises and multiple rounds of M&A.

“They are frustrated with us,” she says of bankers, with a chuckle. But Clearfield, she likes to insist, “will not grow on other people’s money.”

“One thing I have made sure to point out is that we are an old-fashioned company that believes in making money,” says Beranek.

Clearfield was created in 2008 as a carve-out of a prior company, APA Optics, that had made a wide variety of fiber optics components, and that had never made money in the twenty-nine years prior to Clearfield.

Having left that legacy behind, and with a sense of mission built on practical products, Beranek makes clear the company is not going back to those days.

“We built the company to make money, and that’s the intent going forward.”

Clearfield stock is up fifty-four percent this year at a recent $37.56.